Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Redefining Medicaid

There is a lot going on with Medicaid these days, but the biggest change may be with Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers for work or community engagement.

We frequently read or hear the terms “work requirement” and “community engagement” interchanged. For the most part, they are the same type of requirement. A state makes the receipt of Medicaid contingent upon activities performed by the beneficiary.

These waivers were borne from the 2010 Affordable Care Act, which in 2014 made Medicaid expansion available to states that elected to receive an enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) in exchange for providing Medicaid coverage to adults age 19-64 whose income fell below 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

The Challenge

- Participation in some states rates have far exceeded projections.

- Costs per person were 76 percent higher than anticipated[1].

This put more financial pressure on the states and the federal government than anticipated.

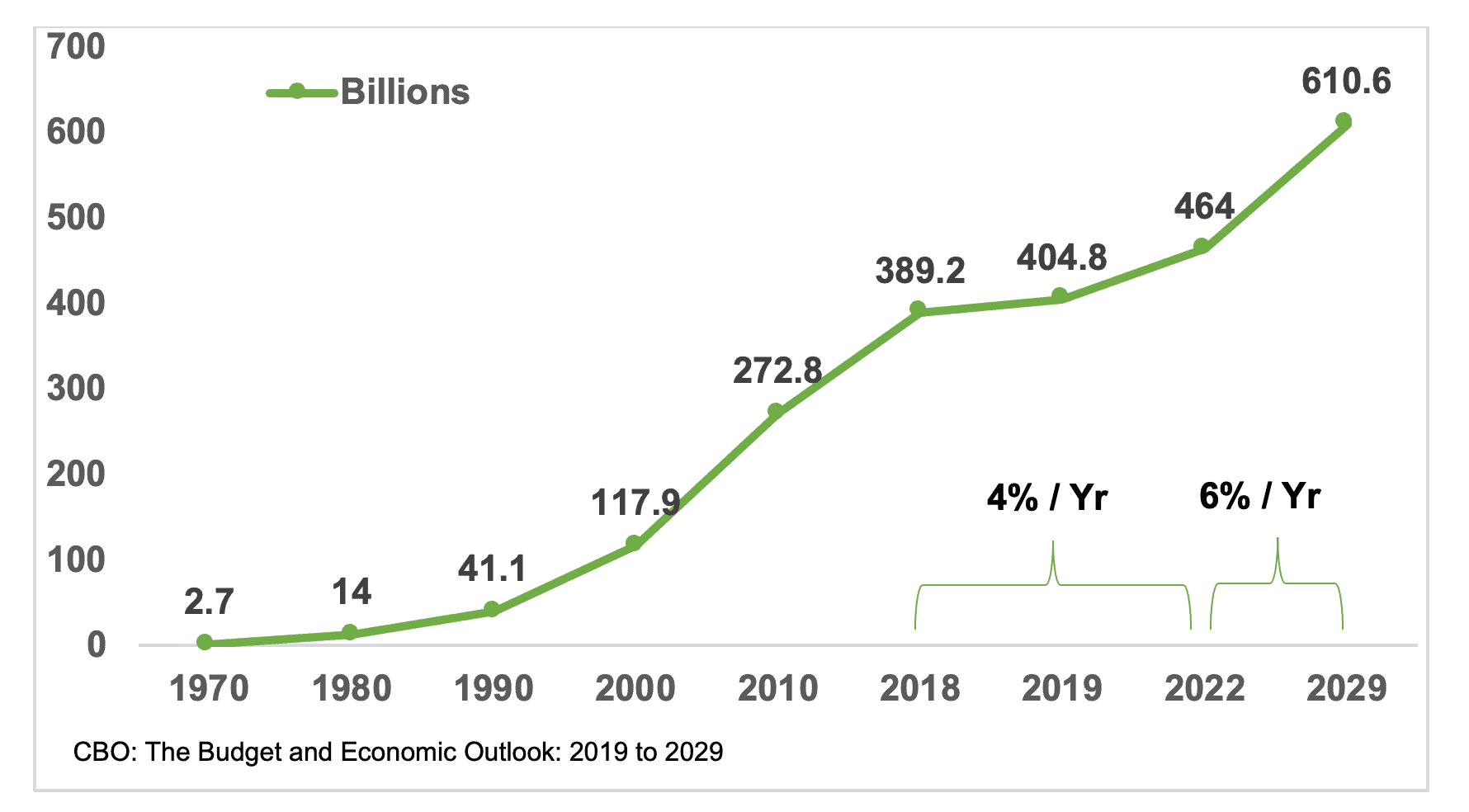

Table 1 illustrates actual federal expenses for all Medicaid populations, in billions of dollars, through 2018 and estimated expenses through 2029. The sustainability of the Medicaid program is of concern to states and the federal government.

Table 1: Federal Medicaid Outlays 1970-2029[2]

This approach to Medicaid has been a focus since the current Administration took office in 2017. In March of that same year, former Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Tom Price sent a letter[3] to the governors stating, among other things, that “The best way to improve the long-term health of low-income Americans is to empower them with skills and employment. It is our intent to use existing Section 1115 demonstration authority to review and approve meritorious innovations that build on the human dignity that comes with training, employment and independence.”

By November 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Division of HHS responsible for oversight of the Medicaid program, had revised the 1115 Waiver criteria.

The focus shifted from:

- Coverage, outcomes, providers and provider networks, and care for Medicaid and low-income individuals or populations.

To:

- Access to services, Medicaid’s sustainability, health determinants, beneficiary engagement, alignment between Medicaid policies and commercial health insurance products, and delivery system and payment models.

Gone completely was the language specifying Medicaid and low-income individuals or populations, and instead was replaced with simply individuals, beneficiary, or not noted at all.

Section 1115 of the Social Security Act gives the HHS Secretary broad authority to waive certain Medicaid requirements. States submit an 1115 Waiver application requesting permission to test innovative approaches to serving their Medicaid beneficiaries. It is the Secretary’s responsibility to determine if the state’s program is likely to promote the objectives of the Medicaid program.

These Medicaid objectives are at the center of the argument both for and against work requirements:

“For the purpose of enabling each State, as far as practicable under the conditions in such State, to furnish (1) medical assistance on behalf of families with dependent children and of aged, blind, or disabled individuals, whose income and resources are insufficient to meet the costs of necessary medical services, and (2) rehabilitation and other services to help such families and individuals attain or retain capability for independence or self-care[.]”

- Section 1901 of the Social Security Act

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396-1 Appropriations

Kentucky was the first state to gain CMS approval for work requirements. But work requirements aren’t the full story! Kentucky’s waiver also authorized the ratcheting down of Retroactive Medicaid from 90 days to the month of application, the addition of monthly premiums, and coverage lockouts for non-compliance. The Kentucky 1115 Waiver included an estimate that 95,000 Medicaid beneficiaries would lose coverage over a five-year period. A lawsuit was filed claiming HHS’ approval was arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedures Act (APA).

U.S. District Court Judge James. E. Boasberg ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, taking into account the waiver in its entirety, not just its work requirements. Using the two-step Chevron framework and 42 U.S.C. § 1396-1 for the Medicaid objectives, Judge Boasberg determined that Congress appropriated funds to furnish 1) medical assistance and 2) rehabilitation and other services. So, what does “furnish[ing] . . . medical assistance” mean? The Medicaid statute “defines ‘medical assistance’ as ‘payment of part or all of the cost’ of medical ‘care and services’ for a defined set of individuals.[4]” Congress’ intent was to pay for medical treatment for needy persons. This includes the expansion group legislated under the ACA.

HHS Secretary Alex Azar argued alternative criteria, focusing his defense on the second half of the Medicaid objectives, notably “attain[ing] or retain[ing] capability for independence or self-care.” He failed however, according to Judge Boasberg, to adequately analyze coverage, and consider whether the Kentucky waiver would cause recipients to lose coverage or help promote coverage. The judge determined he never took in to account the 95,000 Medicaid beneficiaries that Kentucky estimated would lose coverage over the five-year period. Because this was a Judicial review of agency action for procedural correctness and not about the legality of work requirements, Judge Boasberg vacated the Secretary’s decision and remanded the waiver back to HHS.

Judge Boasberg presided over three more 1115 Waiver work requirement lawsuits; in Arkansas, New Hampshire and another one in Kentucky. Each time the HHS Secretary’s decision was found to be arbitrary and capricious. HHS chose to appeal the court decisions for Kentucky and Arkansas. The request for an expedited hearing was granted and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit) is expected to hear the case and make a decision by year-end 2019. That would be enough time for the Supreme Court to hear the case and make a decision in 2020.

There is much, much more to the HHS Medicaid story! According to some experts, work requirements, premiums, and waiving retro coverage aren’t legal. That is a much broader issue that has not been addressed and will need to be answered down the road. The impact of that decision will be far-reaching.